This post presents my research proposal for my MSc thesis: “Predicting the rate of Acute Flaccid Paralysis in different settings to support polio surveillance and elimination”.

- You will learn why non-polio Acute Flaccid Paralysis (NPAFP) is important in support of polio eradication.

- The current challenge involves interpreting the AFP indicator that exceed the targeted levels.

- Potential data sources and modelling methods are raised to fill this knowledge gap.

Aim and Objectives

Research Aim

To investigate and model the mechanisms underlying the notification of the key polio surveillance indicator - NPAFP rates in endemic and outbreak settings.

Research Objectives

- Review and consolidate existing evidence about the possible aetiologies of AFP in population aged less than 15.

- Identify the most informative predictive features for NPAFP rates in WPV-1 endemic countries and a selection of cVDPV outbreak countries.

- Building on the potential causal mechanism of AFP, modelling the expected NPAFP rates at both national and subnational levels.

Background

Polio Today

Since the global efforts initiated in 1988, wild poliovirus has been very close to global eradication. Endemic transmissions of wild poliovirus type 1 (WPV-1) is restricted to certain regions in Afghanistan and Pakistan. There are also episodes of circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV), mostly notified in World Health Organisation African region (AFRO).

The WHO Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI) sets the gold standard for detecting cases of poliomyelitis. The key indicator, the sensitivity of surveillance, is defined at least one case of non-polio AFP should be detected annually per 100,000 population aged less than 15 years. This is the minimum level for certificating a standard surveillance system, which indicate the probability that polio infection will be detected given that infection is present in the population. To ensure higher sensitivity in endemic regions and during polio outbreaks, the NPAFP rate should be two per 100,000 and three per 100,000, respectively (GPEI, 2021).

AFP Notification

AFP is characterized by repaid onset of gait disturbance, weakness, or trouble coordination in one or several extremities. The symptoms can progress to maximum severity within 10 days, frequently encompassing weakness of the muscles of respiration and swallowing. Every AFP case, as a result, poses a clinical emergency. It requires immediate neurologic examination to narrow the differential diagnosis, often involving electrophysiologic studies (Marx et al., 2000).

Poliomyelitis is not the only cause of AFP. There many other causes, including Guillain-Barre syndrome, non-polio enterovirus, other neurotropic viruses, and acute traumatic sciatic neuritis. These potential causes of AFP are often associated with anatomic-morphologic changes or specific pathophysiologic mechanisms. Confirmation of either polio or NPAFP can only be achieved through collecting and testing of stool specimens from AFP cases within the Global Polio Laboratory Network (Tangermann et al., 2017). In other words, appropriate testing AFP, regardless of its presumed etiology, is an integral component of polio surveillance (Marx et al., 2000).

From a macro perspective, the reporting of NPAFP may be associated with multiple factors within a sequence of events. These events include: (1) the necessity for a susceptible individual to be effectively exposed to the pathogens or causes mentioned above, (2) onset of symptoms, (3) seeking healthcare (accompanied by parents), (4) notification as AFP, (5) collection of stool specimens, (6) sample transportation, and (7) laboratory examination (Tangermann et al., 2017).

Across these sequence of events, factors such as dwelling environment (related to climate, sanitation, and access to healthcare services), susceptibility (related to immunity and underlying prevalence), strengths of the surveillance system (related to technical, laboratory ,human, and financial resources) may play crucial roles. For instance, Pakistan and India’s NPAFP rates have been observed as having some association with polio vaccine uptakes and polio cases, respectively (Dhiman et al., 2018; Molodecky et al., 2017). Besides, factors associated with an increase risk of poliovirus outbreaks have also been identified (O’Reilly et al., 2017). The interactions between polio campaigns and health systems were also illustrated through a causal loop diagram (Neel et al., 2021). Nevertheless, there remains a limited understanding and approach to quantify the associations between AFP notifications and various factors throughout the continuum of surveillance events, let alone establishing causal inference.

Challenge

The current gold standard of NPAFP rate to define a well-operating poliovirus surveillance system might be challenged. First, from the perspective of certification, zero-reporting doesn’t necessarily imply the absence of the underlying (latent) numbers of polio cases in a population. For example, an incorrect declaration of polio elimination almost occurred in Nigeria in 2016, following a track record of 730 days polio-free (Adamu et al., 2019; Bell, 2019).

Second, in response to outbreaks, a cross-country study indicates that maintaining a high rate of NPAFP is essential to timely detection of cVDPVs outbreaks (Auzenbergs et al., 2021). It is critical for community health workers in outbreak regions to know how effectively the AFP surveillance systems monitor and identify cases, coupled with environmental surveillance.

Third, concerning international movements, no country can be exempt from the risk of imported polio cases. A WPV-1 confirmed case was reported in Malawi in 2017, which was genetically linked to WPV-1 transmission in Pakistan (2022). This underscores the ongoing risk of international spread until the objective of global polio eradication is attained. Countries that fail to report NPAFP rates after certification may require assessment.

Statistics

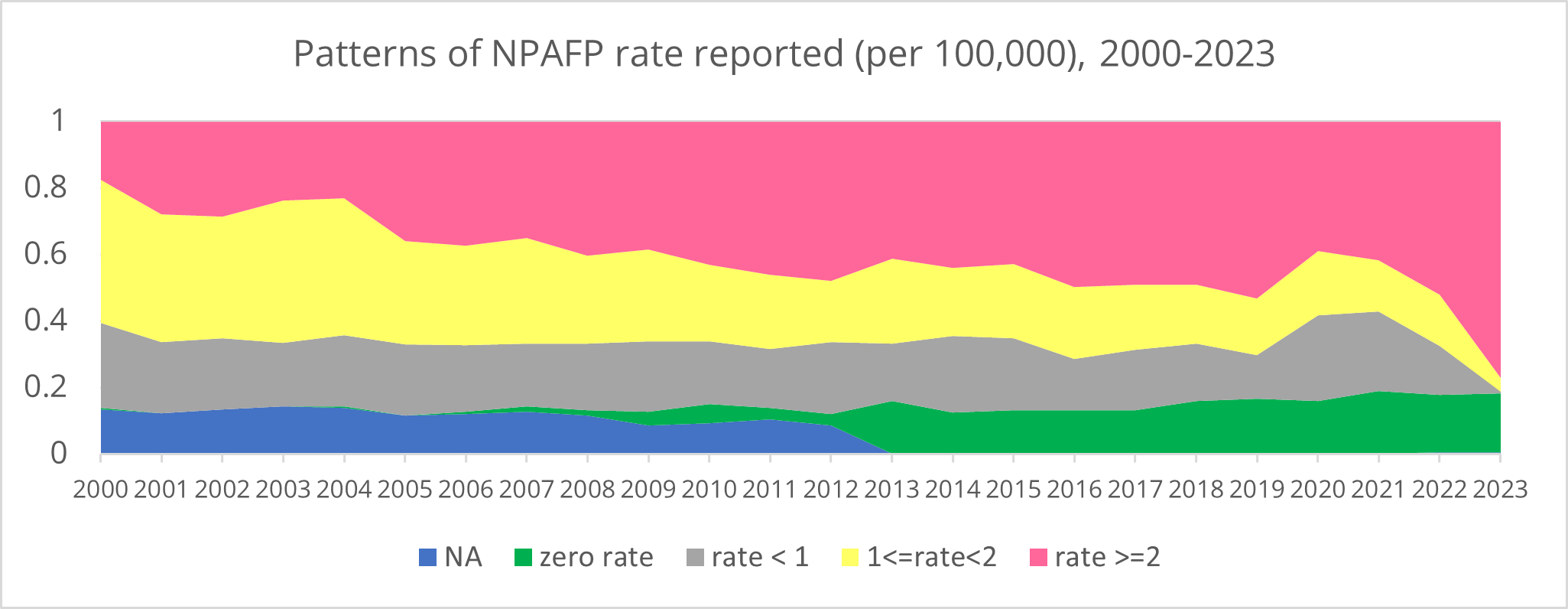

According to the WHO’s open data (Figure 1), it is observed that in 2000, the NPAFP rate falling within the range of 1 to 2 per 100,000 accounted for the largest share (43%) among the reporting countries. Over the years, there has been an increase in the proportion exceeding 2 per 100,000, with 77% of countries’ NPAFP rates surpassing this standard in 2023.

Diving into the data distribution, the median NPAFP rate of the annually median from the reporting countries is 1.7 per 100,000. However, this century ‘s maximum NPAFP rates by year range from 3.8 to 373.9 per 100,000. This wide range is accompanied by an increasing standard deviation in recent years. This right-skewed distribution of data poses a challenge to properly interpretate changes in NPAFP rates, as it reflects different strength of surveillance in different contexts. Notably, the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic could potentially shapes the healthcare landscape, as well as the polio surveillance systems (Niaz et al., 2023).

| NPAFP rate (2000-2023) | Min | Q1 | Median | Mean | Q3 | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual Median | 1.3 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 1.9 | 19.3 |

| Annual Mean | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 37.2 |

| Annual Maximum | 3.8 | 9.2 | 15 | 30.4 | 22 | 373.9 |

| Annual SD | 0.8 | 1.4 | 2.2 | 4.5 | 3.4 | 53.6 |

Mission

Building on the partnership with the GPEI (on behalf of WHO), this project uses GPEI’s database, originally owned by the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The AFP data (including polio and non-polio cases) cover a comprehensive time (> 20 years) and space, including WHO AFRO, Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO), and Western Pacific Region (WPRO). For the purpose of polio eradication, this project’s data landscape focuses on the WPV-1 endemic countries, Afghanistan and Pakistan, coupled with cVDPV outbreak countries, such as Nigeria. Publicly available data will also be collected and analysed as potential predictors at national and subnational levels.

The added value of this project is to offer insight into the reconsideration of GPEI’s key surveillance indicator - NPAFP rate. This project can also contribute to the component of the Free From Infection (FFI) framework of the broad SPEC project. By understanding the sensitivity of the different components that make up the detection process, this project aims to answer what rate of NPAFP should be expected in the under-15 group, either for retrospective data analysis or for future projections. If study countries consistently reports zero polio cases for a certain period, with NPAFP reporting rate exceeding the expected NPAFP rate, this can serve as evidence of the successful interruption of poliovirus transmission.

ADDED VALUE: By assessing the target rates of reported NPAFP among the under 15 population in endemic regions, this project’s value lies in defining a well-operating surveillance system, and identifying regions at risk of under detection.

Furthermore, through the comparison between reported and expected NPAFP rates, it can also identify the weakness of surveillance systems and informs resource mobilisation during different phases, including outbreaks, eradication, and post-certification. Therefore, within the framework of the Polio Eradication Strategy 2022-2026 facilitated by GPEI, this project has scientific importance in providing essential support for surveillance activities and certification outlined in the strategy’s timeline.

Methods

Outcome Measures

The NPAFP rate per 100,000 in children aged less than 15, which is GPEI’s number of NPAFP cases divided by the annual under-15 population size according to national statistics.

Predictors

The absolute number of AFP cases is likely to vary substantially between populations due to a number of factors. Predictors to be assessed including:

- Geographical: (1) urban, rural, or conflict zone, (2) districts bordering, (3) temperature, (4) precipitation, (5) risk of diarrhea.

- Demographic: (1) population size: fewer than 50,000 children under 15 years of age may not detect AFP every year (WHO, 2022), (2) population density, (3) migration and movement (displacement), (4) socio-economic (poverty and barriers to access), (5) total births, (6) gender proportions.

- Surveillance and healthcare system: (1) healthcare services quality, accessibility, and affordability (out-of-pocket payment), (2) Electronic surveillance technology, (3) sensitivity of laboratory testing methods, (4) environmental surveillance, (5) number of SIA campaigns, (6) human resources of community health workers, (7) health financing, (8) performance assessment or reward for reporting, (9) unit of reporting (number of offices/hospitals), (10) pre-and-post COVID-19 pandemic.

- Biological: (1) non-polio enterovirus rate, (2) Guillain-Barré Syndrome prevalence, (3) polio confirmed cases and type.

- Immunisation: (1) OPV and IPV vaccination coverage, (2) OPV and IPV vaccines administered, (3) switch from tOPV to bOPV.

Models

The time interval within the scope of the method may be monthly, 6-month, and annually, whilst geographical scale may be applied to district, country, and continent level. A sequential process from risk exposure, probability of present AFP disease, seeking healthcare, notification, stool collection, sample transportation, to laboratory results will be considered throughout the analysis. The models to be implemented are as follows:

- Machine learning methods, which are robust to high dimensionality and potential dependencies between predictors (dependent on what kind of indicators can be obtained across all geographies). This may include penalised regression (Lasso and Ridge), tree-based methods (random forest), or super learner.

These methods focus on learning complex and non-linear relationships. They can assist in subset selection and variables selection, given the wide range of variables in this project. They can adapt to intricate patterns but may be prone to overfitting, especially with limited data; hence it is crucial to find a bias-variance trade-off.

- Regression based approaches accounting for spatial and temporal dependence. This may include generalized additive models (GAMs), splines, autoregressive models, and Poisson mixed-effect model.

These methods focus on parameter estimation based on assumed relationships, also allowing non-parametric fits with relaxed assumptions. Past values of the variable of interest may be considered. Coefficients in these models may directly represent the impact of each variable on the dependent variable.

- Methods to evaluate out-of-sample predictive ability of models. It serves as an validation purpose.

This MSc summer project is under the SPEC (Surveillance Modelling to Support Polio Elimination and Certification) project work package 1: Surveillance Modelling, led by Dr. Kathleen O’Reilly and supervised by Dr. Emily Nightingale at LSHTM.